Wiebe: “Time to go to the show.”

I’m not tired, but I long for home. Normally at this time I’m answering my emails and writing pieces. I’ll have to miss my messages tonight, because it’s getting later and later.

The Capriccio is a fake joint, that’s my first impression: fake lighting, fake music, fake cheerfulness, and fake boys. We’re still too early for the show, but we’ve been warned: you’d better come a bit early, because otherwise it gets packed. And indeed, we’re just in time, because more people come in behind us. They’re making it busy at the coat check.

It’s a small place, and you can’t imagine that so many people can already fit inside, and more are still coming. Where will they have space to perform later? Yellow neon lighting, eighties music, exaggerated people with blue drinks. A group of German tourists, but you find them everywhere. A boy who has applied a concrete-colored foundation, and has drawn on his eyelashes with pencil sits leering meaningfully at me, and then looking into his glass.

“Will you buy me something?” That’s how I think I may decipher his body language. I shudder involuntarily and pointedly look away. An entire corner is occupied by gentlemen with ties, who fade into insignificance in the company of some heavily made-up transvestites, or drag queens for the Dutch reader. Fishnet stockings, tiger outfit, killer heels, platform shoes, boas. The whole deal. Long-haired wigs, provocative makeup with glitter.

One is dressed almost entirely in plum-colored ostrich feathers, very dark lipstick, with hollowed-out male thighs. There’s no laughing. They’re deadly serious. That one straightens her stockings, the other admires her long false eyelashes in a small mirror. A red-haired giant sits apparently drying her nails all evening with limp wrists with a cruel pout.

They chew gum boredly and let themselves be admired by their male entourage. They smoke long thin filter cigarettes, drink through straws from large glasses and spread an atmosphere of endless fabric that gets too little ventilation. They know no purpose in their lives, except to be visible to others, fruit of their own design, in an eternal struggle against decay, the wear of costumes, the right washing products. No longer people, but useless sculptures.

“C’est celle qui ne l’a pas qui l’a” says Lacan, not that it matters. It’s not exam material. So they stand lazily bitching at each other, until an imperceptible signal is given. Various figures sneak away, while the light goes out. The customers stand, because if you sit, you see nothing. A cheerful soundtrack announces the show in bombastic terms. An elderly transvestite in a white pleated skirt climbs surprisingly nimbly into the light tower to operate the spotlight.

The light goes on and off. All attention turns to the back of the room, which thus becomes the front. The spotlight falls narrowly focused on the closed red curtain. “Mesdames et Messieurs.” The soundtrack is underscored with sound and light effects. The introduction bursts with drawn-out bombast, until finally the curtain rises, for a minuscule stage, where just now there was still the raised dance floor.

The show begins with unconvincing Andrews sisters. One of the three could be Fernando. I’ve seen many Andrews sisters come and go, but this didn’t look like it. Rhum and cocaaa cola. To my great astonishment, however, the room is wildly enthusiastic. It is without any doubt the regulars who cause this applause.

When Shirley Bassey appears in fake gold lamé, I think “that must be him or her.” The tallest of the bunch. Goldfinger. The number never comes to life at any moment. I look around and ask one of those present, the one who seems blessed with mental life, casually. “What’s this artist’s name?” “Mais, C’est la Cucaracha!”

“Do you know her real name?” “C’est Fernando Van Quelquechose. C’est un Flamand brésilien.”

The rest is lost in the distorted voice of Shirley Bassey, copied from a worn-out gramophone record onto an old cassette tape, it seems, from the time when CDs didn’t exist yet. The sound quality is simply terrible.

Intermission

Wiebe: I can only get nostalgic about it.

But well, we didn’t come here to amuse ourselves. I’m thinking of a way to get in contact with Fernando after the performance. During the intermission I manage to squeeze myself next to the elderly transvestite with the white pleated skirt, who has come down from the light tower.

She bares her porcelain teeth while her mouth corners seek the vicinity of the earlobes. It gives the aging face a special ‘éclat’ or radiance, or let’s say a lift. “Bonsoir, ma belle. Shirley Bassey etait fabuleuse.” She knows I’m lying.

“Elle a de l’expérience” she says, not to say, “She’s getting old too.”. How do I get an autograph of the star? An autograph you know? “Mais ce n’est pas un problème. Elle boira bien un verre de vous au bar.” She will probably drink something from us. Right now, a feeling of dread overwhelms me. I don’t know what for. I’m afraid of finding a Ricky I didn’t already know. I never quite knew what other people he saw yet.

Of course he had other friends, but he managed to keep that reasonably separate despite all his chaos. He led a hidden life. I never knew where he bought his drugs for example. He preferred to use them in the toilet, so no one could watch him. Ricky could sometimes stay in the toilet for tens of minutes, so that his absence became painfully obvious, especially when others were present. Or you wanted to go to the toilet yourself and there he was.

After his release from prison, Ricky came to stay a few times, but I preferred that he wasn’t there all the time, especially not when I couldn’t be there myself. I do work, after all. I don’t know why I didn’t want to take him into my house. Had I lost my trust in him? Was it out of fear of his drug past, or because Ricky was so touchy those first days?

He reproaches me for my hardness with few but venomous words, and with a harmonica blues on the terrace of the apartment. It was a bit shrill. The weather was the same then as now. Ricky was completely clean, and deeply unhappy, immersed in a depression whose bottom is not in sight.

The agreement was that he would stay clean and drug-free outside prison too. That apparently didn’t work out, with what we know now. He aged a notch in there, and lost much of his boyish charm. He also acquired a bitter tone. He shows even more despair than before, even more colorless, dark clothes, even more melancholy.

He’s afraid of sounds. He drinks gallons of coffee and smokes one cigarette after another. “You’re smoking yourself to death” I say. And “We need to go to the doctor or the psychiatrist.” It all achieves nothing. It doesn’t get through to Ricky. He had no friends anymore. Except Fernando. “Before he ended up in black leather, Ricky himself spent a few months in the transvestite milieu. It was a phase. That Fernando has something to do with that.”

Brigitte is genuinely surprised. “Do you really think so? In the transvestite scene? Ricky? He didn’t tell me that.”

“Who tells their mother everything? He had much admiration for that boy, for his willingness to make choices. Fernando is an instinctive survivor. Ricky kept everything else largely hidden from me too. He never said anything about it. I never pursued it, so as not to become even more jealous than I already was.”

It’s the same jealousy that makes me furious at the death that abducted Ricky. Death, the unbeatable rival. That he has the last word, I cannot accept. That’s precisely why I’m biting into this case. Sometimes I think I see Ricky walk past a lamppost or stand in a bus shelter. Tall and bone-thin, possessing a steadily shrinking beauty, wrapped in a black leather jacket and jeans, shivering in the cowhide, desirable and unreachable. “The wind blows right through it.”

I will survive

The second part of the forgettable show:

Fernando brings Gloria Gaynor to life in the immortal gay anthem “I will survive”. I don’t know how it happens, but it gets more and more fun. The sound is perhaps of better technical quality than that of Shirley Bassey. Or Fernando, alias la Cucaracha, is simply doing better. Or because it’s a black number. Fernando seems to have become a different artist. Maybe she snorted a line. She gets the whole room going.

Everyone goes wild at the finale of the drawn-out number. Then it’s over very quickly. After the final scene, the majority of the audience has immediately disappeared, so you can breathe again. We wait tensely. After a few numbers from the jukebox, an unmasked Fernando jumps off the raised dance floor with a sports bag. He sits on a stool at the bar and I offer him a drink. Fernando is a slender boy. Without makeup it’s noticeable that he looks tired, and shows a tragic beginning of aging.

“Can I ask you something?”

“If you must.”

“Does the name Ricky van Genechten mean anything to you?”

His face contorts. He lights a cigarette. “No, I have nothing to do with that.” Everyone feels that he’s lying. “Sir, we would be very grateful if you would help us.”

“Help, help. Who helps me? I’ve always had to do everything alone too.” He sits a bit whorish on the bar stool, and forgets for a moment that he’s dressed in men’s clothing. “Would it be useful if we were to place a small sum in your hands?” Fernando studies the ceiling diligently. Rafels looks up strangely when I ask him to advance the money. “Give me a hundred euros?” “What?” “Don’t you have a hundred euros? I only have my bank cards. I’ll pay you back.”

Rafels discreetly takes €100 from my wallet in two fifty-euro bills, and I pass them invisibly to Fernando, who carelessly lets them disappear into his clothing. “What do you want to know?”

“Tell us about Ricky? What happened to him?”

“Ricky is dead.”

“We know that. But how and why?”

“I can’t tell you that. Then I’ll be killed myself. Just like they killed him.”

“Who are they?”

“You should ask Robeyns. Robeyns knows everything. But don’t tell him you got that from me.” He looks around nervously, as if he fears being eavesdropped.

“Which Robeyns?”

“Not so loud. Le superflic. Go away now. I’ve already said more than is good for me. Ricky and I, we did stupid things. On a fait des bêtises. He told me a lot, but I am silent as the grave. I don’t like to be reminded of it. On a payé. We have paid the price, both of us. It just has to end.”

“Can’t we meet somewhere quiet?”

“I’m dog tired. I can’t anymore. I still have to get a shot and go to bed.”

“Listen, come to the lobby of the Hilton Hotel on Monday afternoon. You can earn another hundred euros.”

“Well, if you say so.”

“Are you coming?”

“What time. Two o’clock in the afternoon? Does that suit you?”

“Monday at four o’clock. I need sleep.”

“Another question. Do you know an Abdelhak?”

“He works in Paris, in the Homodrôme to my best knowledge. But now that’s enough. Don’t talk to me about Abdelhak. I hate that boy. I hate him. Don’t speak that name again if you want me to come. That’s enough for tonight. We’ll see each other at the Hilton.”

He jumps off his stool and a man with a tie detaches himself from the wallpaper. Together they go out the door. Apparently Miss Daisy has her own chauffeur. We go home. While I’m taking Brigitte and Wiebe away in the blue BMW, I notice that I’m being followed once again by a grey Citroën. There’s little traffic at this late hour.

I decide to drive around the block to see if it is him. And yes, he follows me through the tunnels until Louisa Square. There I get out and take the tunnels back toward the Basilica.

“What are you doing?” asks Brigitte. “You’re going all wrong.”

“It’s that grey Citroën. I encounter it everywhere. It’s following me. I’m trying to lose it.”

I drive to the center to be able to see clearly in the well-lit boulevards what car is driving behind me. It’s still the grey Citroën. Apparently he gives up when I drive into the small streets around the beguinage, and shortly after race around the Sint-Katelijne church in the wrong direction. He’s lost a few seconds before he realizes it. I look for a short side street to turn off.

Hilton

Listless atmosphere.

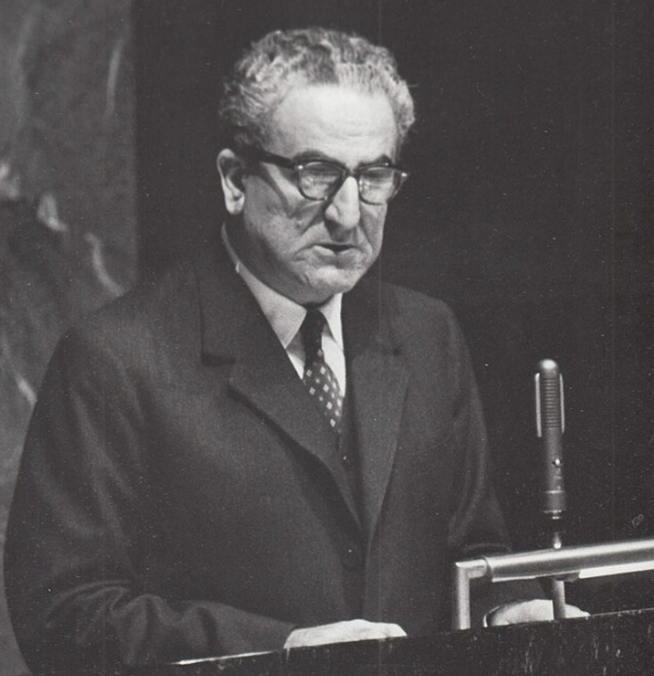

At the Hilton we have plenty of opportunity to catch up with each other, because Fernando of course doesn’t show up. Wiebe has an unpublished photo of Ricky with him. “This snapshot fell out of a book this week. I didn’t know I still had it.”

Ricky in white t-shirt, in black and white, in his best days: a handsome young man, radiant with promise.

Brigitte finds the opportunity to complain once more about the Van Genechten family. “What bothers me most is the indifference of those people. Whether it’s about Caroline, or the men. Just when he was having such a hard time, she stopped depositing money, without questioning the consequences of her actions.”

In her eyes there’s no difference between one Van Genechten and another, in her eyes a damned race, where everything revolves around money. “Strangely enough, Ricky inherited that family trait and it destroyed him.” Brigitte has newspaper clippings with her. As he grew up, the Van Genechten family fortune multiplied many times over.

The articles cover the ups and downs of the glass industry.

In later years there are more and more reports about Bernard Van Genechten, who is making headway in politics.

Around Bernard hangs in the press a whiff of old-fashioned corruption, patronage, taking advantage, handshake deals, but he’s never officially suspected of anything, so you can’t write it.

“They’re all heartless people.” There’s silence. At the beginning of the conversation, Brigitte told us that she has decided to return to France, now that the floods are receding, to pick up the thread with her own life again. Her savings are gone and she has to get back to work. There’s another silence. There’s no momentum in the conversation.

Around us the hotel buzzes in unceasing activity.

Brigitte is lost in reverie. Wiebe also falters, and we sit mindlessly stirring our coffee, while we wait for Fernando. It’s beginning to look like Ricky led a life that neither Wiebe nor his mother knew about.

“Do you think Ricky ever met his father?” I ask. It’s as if she startles from a daydream. Brigitte stammers something and has difficulty understanding the question. For a fraction of a second she suddenly looks much older, her features relaxed and sagging, but the affected flash is quickly past. She recovers.

“In recent years we didn’t talk about his father anymore. When Ricky was old enough, I told him about the agreements and the contract.” We received money from Caroline and in return were not allowed to undertake anything to approach the family. It was clear that they had to pay back all this money if we didn’t comply with the terms of the contract.

“After this was clarified, we didn’t talk about it anymore. However, it weighed heavily on Ricky. I think. It was as if he was ashamed that he grew up without a father. Until the moment I went to visit my son in prison. He said with a strange grin that he could still ask his father for help. “I’m going to my father when I get out of here. I’ll show him what kind of son he has!”

“Don’t do that now.” He never pursued it. He had a mobile mind, so volatile that he didn’t always have solid ground under his feet. Ricky didn’t easily find the right words. Under his somewhat awkward exterior slumbered a sharp intelligence. You didn’t always know what he was up to, but he did come to mature judgments about people.”

It leaves a bitter aftertaste, a harsh life story, of loss and adversity. Wiebe says what everyone thinks. “That Fernando isn’t coming anymore.” A last cigarette, and we leave. Soon the blessed moment of the last drag has also passed.

To be continued…

Recente bijdragen

Racism in opera – avoid clichés and commit to inclusiveness

Taking racial elements out of opera Reading time: 5 minutes. Avoiding racial stereotypes in opera requires a thoughtful approach. Directors may […]

The UDHR – Charles Habib Malik’s ecumenical vision

Charles Habib Malik’s ecumenical vision Charles Habib Malik (1906-1987) was an influential Lebanese academic, diplomat, philosopher and […]

Back from the road – Florida

Florida Was Wonderful I don’t love America as a power, but I adore Americans. The way they interact with each other—we cold […]

No comments have been posted yet!