Funeral ceremony

For Wiebe, the whole story began a year earlier, in 1997.

I can still see myself walking on Steenstraat. It lay torn up, a stone’s throw from the Stock Exchange, in the shadow of the Kladderadatsch, which hadn’t yet gone bankrupt, nor been taken over by the French-speaking Ministry of Culture.

An early Saturday evening full of promise. Cars in the splashing rain. Typical Brussels ambiance. There’s a tingle in the air. I walk to a café on the corner of Steenstraat and the Boulevard, where I sometimes come. High windows let light out. Seen from outside, it looks like an overcrowded birdcage full of magpies, black jackets and white t-shirts, above jeans admittedly.

I stood for a moment on the other side of the street. Now and then the door opens and a wave of pop or rock music comes out. I’m not much of a connoisseur of pop culture. Men of various origins and different skin colors stand leaning over the round bar, or they sit at tables in the right wing of the bar room. On the left are the slot machines.

Working-class types predominate, bordering on ethnic. Taxi drivers and day laborers from all continents, let’s say. No one looks up when I enter in my black weekend jacket. Sidelong and furtive glances do shoot back and forth. Everyone here looks sideways, and no one looks you straight in the eyes.

There’s a bar stool free. I sit on one cheek. I look around a bit and let the space work on me. The music switches from the Flemish schlager “Someone Has Hurt You,” to something eastern but with a good beat. Cheb Khaled perhaps, with such a North African voice. Most men drink lager or cola, a few are wasting money at the slot machine. Many smoke American cigarettes.

A single woman shines in her décolleté. She’s a blonde chick with big tits and an Olympic ass, who sails through this milieu with an inexplicable mental superiority. The many men treat her companionably and barely look at her. She’s probably wearing a wig.

I shudder involuntarily.

It takes quite a while before someone takes my order. Behind the bar, a playful spectacle is going on between the bar owner, a bald fat man of advanced age, and two young Maghrebis who assist him in his task.

I’ve already had more than one drink since early evening, but I order a new one. Young gin. It tastes a bit nasty and I get a bit dizzy. Fast forward.

I want to get up and turn from my stool, which turns out a bit higher than I remember. Thus I accidentally bump into a guy. I just barely avoid falling, by clinging to him, I immediately take a step back in recovered balance. I look at him and he looks at me in a long eye glance, and gaze strike, a lightning strike. Slow motion until the image freezes and solidifies.

I can’t say anything for a moment, which rarely happens to me. “Did I hurt you?” Something silly like that. “Did I wound you or something? Je t’ai fait mal? Did I hurt you?” Turn it off, the Repeat button, now.

You never know here in which language you should start. He signals ‘no problem,’ with a sunken gaze in deep eye sockets. This first moment does me no good. It’s as if I get hit with a sledgehammer. You’re still shaking quite some time later. It’s the kind of experience you only encounter a few times in your life.

“I Will Survive” by Gloria Gaynor blares through the speakers, so this must be a magical moment, only it comes about rather shabbily here, after twenty years of experience in gay bars. I try to shake it off. An unnecessary toilet visit and an equally unnecessary order later, I take my place at the bar again. To my horror, the other is sitting next to me shortly after. A game of eye contact develops, and little by little we end up sitting next to each other on a bench.

Ricky and Wiebe

His name is Ricky, as I learn.

“Nice name. Hello, I’m Wiebe.”

“Wiebe, what kind of name is that?” So we make acquaintance over a vodka tonic. Ricky is dark blond and pale, in a black jacket that hangs loosely around him. His trembling skin is stretched over a narrow skeleton under the matte-tanned cowhide. His bare neck emerges from a folded collar of shiny ox leather. It’s fraying at the fold edges. The sheepskin under the jacket cannot hide that he’s cold, because he’s shivering.

I’m not cold at all myself, on the contrary, I’m getting warm. Ricky wants to talk, but not much. He speaks Flemish with a French accent, which comes across as very sexy to me as a Dutchman, because I constantly have to suppress the urge to correct his language use. He’s very down, and he makes no effort to be nice. I try fruitlessly to cheer him up. I’m usually good at that, but this time it doesn’t work. A curl of dark hair falls over his forehead, but I don’t dare touch it.

Yes, that’s how it started. It didn’t even last a year. In the beginning, Ricky was still a student. At the end, things went wrong. He lived off benefits and shady jobs. He wasn’t well off, but showed no desire for more. It seemed as if he was experiencing a permanent state of grace. Until you saw him in his depressive moments. That was like day and night. Sometimes sparkling, sometimes freezing.

Besides his hard body, he only had his harmonica to express himself. He spent more than you can on benefits. He said he had friends with long arms. He sometimes played his harmonica in the metro corridors and if someone gave money, he didn’t refuse it.

It seemed as if he wandered aimlessly through life. He did the occasional job, he said. To Holland for someone. I didn’t ask questions about it, not out loud anyway. When he was a bit groggy and let himself go a bit, he said something about it, but that didn’t happen often. There was a dark side to his existence where he didn’t let me in.

In any case, Ricky died and I can’t live with that. He’s not coming back, but those images from back then all come back, without stopping. It’s taken such an annoying form that I’ve sought medical help. The family doctor diagnosed depression and gave me pills.

I go to the family doctor every few weeks to talk about the treatment and pick up my prescription. So also this afternoon.

I walk somewhat relieved to the pharmacy. I don’t have my glasses on, but I can make out a police uniform waving at me from across the street. “Mr. De Vries?” I think: “Oh dear,” but my fear quickly subsides: it’s our own neighborhood officer. I put my glasses on to study him better. Around fifty, physically a bit worn. Where else do I know this man from?

I have to think for a moment, but I can’t place it. He’s now so close that I have to take my glasses off again. “You are Wiebe de Vries, of Dutch nationality? Well, I’ve come to bring you a summons. Pro Justitia.”

“What does this mean?”

“You will be summoned for questioning.”

“What is it about?”

“I am not allowed to tell you.”

“But now I know where I know you from. I’ve seen you in the waiting room of the family practice. We’ve talked when you weren’t in uniform. Can’t you tell me something? Does it have to do with Ricky? Richard van Genechten?” I can see from his face that it’s a hit.

The neighborhood officer searches for a position. “They’re at it again now. They’re going to investigate it one more time. The inquiry is opened, or reopened. Now they want to know why he died, that Richard.”

“But it’ll be three years soon.” I try to look interested, but I’m getting a bit worried inside. I’m mainly speechless. Louis jumps into the gap and continues: “Sir, may I ask you something? Did you know that guy? Do you know anything about it?”

“Are you asking that from your official capacity?”

“There’s more than that. You know that I found him dead on Charles Baudelaire Street?”

“Ricky?” I find this suddenly degenerating into something unpleasant and I look Louis right in the eyes. Before I can say anything, he resumes: “He probably died from the champagne.”

“Death from the champagne, Louis?”

“Yes, there was an open bottle in a champagne bucket shaped like a top hat with a napkin draped over it. There was a half-empty glass next to it when we found that guy. Sir lived in an uninhabitable building, but he was drinking champagne when he died. That’s how I want to go too, and preferably with a beautiful woman beside me.”

Well, I can’t add anything to that. The thought hasn’t left me since. I have to go for questioning! It literally says so. I’m getting cramped and nervous about it. I feel like I’m going to vomit or cry, I don’t know which first. Something’s not right. It’s as if I’ll never get over it this way. It makes me furious.”

“Cigarette?”

“Thank you.”

Panic

When he left, I really started worrying.

Are they going to question me three years after his death? What have they been doing all this time? What can I tell them? What have I done wrong? We were just two casual boyfriends.

What’s so terrible about that? From the wrong side, probably. We don’t bother anyone, do we? And I never had anything to do with his drugs, did I? I’m just trying to shake it off. I’m trying to pick up the thread of my life. Now this. Haven’t I done enough for him? Where did I fall short?

It doesn’t leave you cold, such a summons. The anger returns in intensified form. As if he’s not completely dead, as if he’s tugging at a line from the depths of dark water, making our float bob. That makes it difficult to get away from it.

Why did he die? Does it only have to do with his drug use? Or is there something else? As a society and as an individual, I think we’ve fallen short.

That’s the result of all the efforts of the parents, the schools, the aid services, the friends, the love and finally the public order, police and justice: a trajectory resolutely aimed at destruction and decomposition through our rock-hard society. He bumped into everything and finally succumbed to his injuries.

He also bumped into me. He always had something of a wounded bird. I was in it for his love, his presence, his friendship, tenderness and sex, because it was indeed a very physical relationship. We grabbed each other. Two rolling stones, rubbing together in the stream of the capital.

It was rock-hard one time, bored and dull the other, and looking back on it now, always worthwhile, even in the sluggish moments. I developed an uneasy feeling of love and concern for Ricky, but I also didn’t want to let myself be swept away too far.

The wild months of the initial period with the endless lovemaking were quickly over. He did his best not to involve me in those drugs. I never had any trouble with it. Could I have done something about it? He went to prison. Was released again. Looked me up. Asked if I could take him in for a few days, but sorry I couldn’t, not longer than a day. He was too wild for me for that.

I didn’t dare. I did pay for a hotel room for him for another week or so, time to find something. I really regret it now, yes. I could have done more. When he came back from prison, he wasn’t the same anymore. I became afraid of him. I was still feeling it out, whether it could click again, when I heard he was dead. I was devastated. I loved him.

When he died, I felt strangely abandoned. He was free in his life choice and it ended in death.

It can’t be made right anymore. Who or what killed him? Did he take his own life or was he murdered? That’s what I’d like to know. I didn’t want to hurt him.

Those were my first words: “Did I hurt you?” But I hurt myself, I fear. I keep dwelling on it.

1998

Wiebe to the Stilte/Silence Stop..

“Rituals are good for processing grief. Ricky’s mortal remains, or what was left after the autopsy, were ‘released for burial or cremation’ by the examining magistrate after many weeks. I hope no suspicions rest on me. I wasn’t in the country when it happened. I insisted to the police that they let me know when he would be buried or cremated. They always assured me they would.

Eventually I call myself, because it takes so long. Someone wants to know if I’m family. They’re quite suspicious. I eventually learn the time and place of the funeral. That morning I take the tram fairly early at Warandepark, with my calla lilies wrapped in glistening plastic.

Line 92 will take me in one go, without transfers, to the cemetery with the crematorium of Uccle, near Silence Street. It’s a picturesque ride. The tram takes you through a part of the Brussels Capital Region that you don’t know at all, because no one ever needs to be there. It’s quite up and down hills, with buildings that open up more as we ride further from the center.

How sloppily the space is arranged here. Complete building anarchy. Not a single structure gives the impression that it has anything to do with its neighbors, and that tram just rides through it, without anything falling over. Land of Delvaux and Magritte, I’m beginning to understand it. As the tram car empties, I notice a woman who sits behind large glasses staring ahead as if she were cut off from the world, though she does wobble along with the jerking of the tram.

However, she never looks up or anything. She’s not dwelling among us.

Not beautiful nor striking, but rather an ordinary woman, in her early forties. A gray mouse, but with a marked face, that’s for sure. Rather neat than truly distinguished. Decent poverty, marked by life. A bit too heavily built and already somewhat sagging, but by now that’s all women past forty, and the men too.

Not me, I stay skinny as a rail, whatever I eat. She wears a hat in waterproof and holds an umbrella. Otherwise she’s in gray: mouse-gray stockings and long mouse-gray coat. The hat doesn’t really go with it and she probably bought it recently. Maybe together with the umbrella in a shop not far from the station. As the tram rushes from stop to stop on the narrow Alsemberg road, it becomes clear that this lady isn’t getting off, and like me is heading to the terminus. The Stilte/Silence Stop.

I can’t figure it out. Eventually it turns out she’s come for the same deceased as I have. I soon assume it must be Ricky’s mother. During the short ceremony at the coffin, I’m the only one with flowers, which then end up on the coffin. Calla lilies, green and white like upside-down, slender leeks.

Further away, an apparently Islamic boy sits shivering on a bench. It’s not clear whether he belongs to our ceremony or the next one, because one dead person follows shortly after another.

The woman stands bent over, with dry eyes, but with an empty gaze. The ceremony, at municipal expense, is minimal, which increases my heartache. Burned like infected cattle, for a pittance. The bells and whistles of Catholic liturgy are cruelly absent here. The funeral liturgy is rich in songs and stories.

Here we get a dry little speech from someone who doesn’t introduce himself and who is probably the director of the cremation committee, or a retired actor, could be. The poem by Vasalis that he delivers, however, is particularly well chosen. The flowers are burned along with him. A bit of dust remains of Ricky.

Recente bijdragen

Racism in opera – avoid clichés and commit to inclusiveness

Taking racial elements out of opera Reading time: 5 minutes. Avoiding racial stereotypes in opera requires a thoughtful approach. Directors may […]

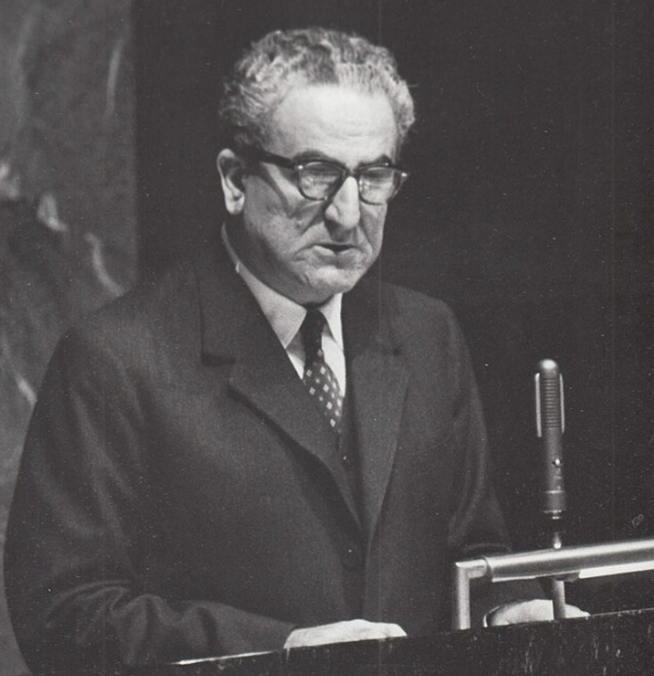

The UDHR – Charles Habib Malik’s ecumenical vision

Charles Habib Malik’s ecumenical vision Charles Habib Malik (1906-1987) was an influential Lebanese academic, diplomat, philosopher and […]

Back from the road – Florida

Florida Was Wonderful I don’t love America as a power, but I adore Americans. The way they interact with each other—we cold […]

No comments have been posted yet!