Doctor Rafels

My turn to take over the story.

Wiebe, for we call each other by our first names, comes to consult me at regular intervals with varying complaints. Physically he’s in good health, but he suffers from stomach pains and sleep disorders, depression, and sometimes more alcohol than necessary. He’s invariably punctual for the appointment and I’m always late.

You get to know each other over the months and years that you deal with someone as a general practitioner. Wiebe is tense this morning, I feel it immediately. He sits tensely on his chair, and has a grim set to his mouth. I look at him and see that things aren’t good. I simply take the ashtray out of the drawer, without comment, for comfort and cheer.

I’ve put away the whisky, but the ashtray lies ready in the drawer, in case Wiebe has cigarettes with him and wants to smoke

Then I simply smoke one along with him. He’s not just a patient, but has also become a dear friend. Smoking isn’t allowed in a general practice, but we do it anyway, because it’s that kind of dreary day, and because right now nothing else can still the fathomless melancholy of this man. Wiebe is increasingly nervous, tense and driven.

It goes up and down but still you can observe a rising trend over recent months in the number of complaints and in the pill consumption. When it goes from bad to worse, he also becomes a bit blunt and aggressive, and occasionally the anger threatens to get out of hand. Then you can say he’s beside himself with rage.

The illnesses of the mind, and their treatment, are still taboo for many people. If you’ve been admitted to psychiatry once, and the cruel public finds out, then you can forget it in politics or public life. Wiebe is terrified that someone might learn he takes something. But what’s the problem, if the medicine you take helps you control your feelings better, fulfill tasks better and have a life of better quality?

Wiebe then is still a mild case, perhaps just too sensitive. He is exposed to a stress that he finds difficult to bear, given the difficulty of grieving.

The illnesses of the mind, and their treatment, are still taboo for many people. If you’ve been admitted to psychiatry once, and the cruel public finds out, then you can forget it in politics or public life. Wiebe is terrified that someone might learn he takes something. But what’s the problem, if the medicine you take helps you control your feelings better, fulfill tasks better and have a life of better quality?

I don’t say much and just listen to Wiebe, also to his silences. The open conversation technique and the red Marlboro bring us closer to the grief, which makes him burst into tears now and then. I’m not allowed to reveal any of this, given professional confidentiality. They’re emotionally deep conversations, but it also seems as if time stands still. The hurriedness settles down, as if there’s time to listen to each other.

Screen

I get distracted.

My little daughter draws attention on the monitor, with moving images playing out in the waiting room. They flicker on a discreetly positioned video screen, beneath the computer. On the small black-and-white square you can see in hard contrast how little Sarah Rafels, my four-year-old daughter, followed by Hafida, my young ex, skips into the waiting room.

This is not without effect on the Arab women sitting there waiting.

Thanks to the ingenious video system I can surreptitiously watch the scene, while Wiebe, who doesn’t notice this, pours out his heart a bit longer. I feel a strong urge to break off the consultation and take Sarah in my arms. I go open a window to dispel the smoke, and suggest taking the blood pressure. The moment of deep understanding is over, but I know we’ll return to this.

A moment later I forget all the sorrow of this planet in the embrace of my dearest little daughter. Of course I have no time for you, busy as I am. But this moment also passes. Someone wrests the child from my embrace, and I come to again. Hafida, the mother of little Sarah, I should say, rises up behind the toddler, in her gnome-like stature. Her commanding gaze demands all attention.

Pretty, petite, natural and dangerous as a supple cat who can spring at my carotid artery before I know it. A golden pendant with a frolicking golden Mickey Mouse hangs askew in her shallow décolleté. Perfectly relaxed, supple, balanced, unconscious of herself, controlled like a predator that can start clawing the next moment. I’m as always completely under her spell, a willing prey in her grip. Can I help it that she has this effect on me?

Hafida, my ex, is essentially a good person, but she doesn’t know that yet, and I still have to teach her. Meanwhile in her youthful enthusiasm she walks over corpses. With stiletto heels if necessary. Fortunately we still have many years ahead with raising our child, Hafida statistically many more than I, given the age difference. I’m afraid of unpredictable demands, especially in the financial sphere. It makes me anxious.

I’ll probably end up shouting by way of reaction, when new figures come on the table shortly, because she regularly thinks of something. Her eyes are already spitting fire and she hasn’t said anything yet.

She’s breathtakingly beautiful in her passion, I must admit that too. That you remain legally separated from that, for the rest of your life. It’s sloppily put together ” Petite, palpitante, mais pleine de tempérament. “

A child-woman, a Minnie Mouse, who inexplicably gives me the creeps, elephant that I am. I seem petrified. We haven’t exchanged a word yet and my knees are already knocking. Ibrahim calls me to order, and gestures with his head that there are patients waiting.

I shudder, and I don’t know why I get nervous from any kind of family. Source of suffering and pain. We’re so vulnerable in our relationships and it’s the same everywhere. That we’re vulnerable means that we’re also hurt all the time, because that’s part of it and it’s the best proof.

Evening Consultation

After dinner I return to the practice.

I shudder, and I don’t know why I get nervous from any kind of family. Source of suffering and pain. We’re so vulnerable in our relationships and it’s the same everywhere. That we’re vulnerable means that we’re also hurt all the time, because that’s part of it and it’s the best proof.

I can see he’s seething inwardly with rage and anger. Nevertheless he gestures that it’s fine, and that I can certainly take another minute. The street door is pushed open by a man with an Arab appearance, who addresses himself to Ibrahim. I leave Wiebe sitting a bit longer and flee inside. The desk looks neat, the computer is on, and the examination room is also tidy.

I use the created time loop to go to the toilet. There I can prepare for the next conversation. I wash my hands, dry them carefully, adjust my tie. I admit I empathize with him very much, so much that I must be careful not to be dragged into a whirlpool of emotions. It sometimes becomes too much and comes too close. But I can’t turn Wiebe away either.

I take it far too much to heart. Ricky died of an overdose. Done. Happens regularly in every city. Mainly to people who don’t find their way to help services. But it’s not my man who was murdered here. Why do I get so involved? On the other hand you can’t just recoil and refuse your help to someone who asks for it, because that’s what you’re a care provider for.

You get talking with someone and before you know it, he’s dead. You’d be shocked by less. Everything seems absurd then. But there’s still nothing wrong with the world because of that. People are unhappy and they die. Wiebe isn’t made of peanut butter and buttermilk like most of his compatriots. He’s coherent and precise, with a preference for information that’s practical and detailed to verify. Everything he says checks out.

He’s steeled and hardened in the toxic corridors of the international administration. Every day he’s immersed in an environment that literally applies the slogan ‘survival of the fittest.’ He’s survived it all. He possesses a sharp eye for human nature and a sharp pen to describe that nature.

I follow the story of Wiebe and Brigitte distractedly, and of the summons, but it seems my absorption capacity is saturated. Then Wiebe leaves again. The evening consultation that follows becomes quite difficult. It becomes a bit too much for me, all those people with complaints. I get tired and I notice I’m getting sloppier, and try to gain time to get them out the door faster. It becomes working through until ten to eight. Only at the end do I discover that I’ve lost my mobile phone. The cell phone is nowhere to be found, not at home and not in the practice, and when I try to call it, it sounds switched off.

Yet I know very well that I had the mobile during the evening consultation, because I got a call from a colleague. After that I put it down somewhere, but I can’t find it anymore. It can only have been stolen.

It’s particularly annoying because now I’ve also lost all my numbers that were stored in the memory, with my whole secret life, which I’ve never told Ibrahim and Hafida about. That’s why I never wrote down the numbers either. Lost all my boyfriends. Not that there are hundreds but still two or three. So they can’t call me anymore either.

The good news is that I can’t be called anymore for urgent jobs, and actually I find that a good excuse. But the cell phone still bothers me. Who takes the doctor’s cell phone?

I file a complaint, but I don’t expect much from it. Two officers come to write it all down. When they’re gone, I lie down on the couch with a pounding head. I try to watch some television to forget it and let it all sink in. It doesn’t help. It keeps haunting my mind.

Ricky and Wiebe and Louis and Brigitte. That dead boy on that couch. What is all this? Why does it all keep coming back? I turn on the television. We already experience misery all day, but in the evening the tube of gloom adds an international dose to it. The News, that doesn’t cheer you up either.

The police reform isn’t progressing. Pigs without foot-and-mouth disease are nevertheless slaughtered in large numbers. Africa suffers. Minister Van Genechten opens a new metro station.

The name rings a bell in my drowsiness. Wasn’t Ricky’s name Van Genechten too? Isn’t there a connection there? It makes me think. But it’s probably a coincidence.

What could the minister have to do with a young man who lived and died four years ago now? There are perhaps many about whom I give no account of their existence or disappearance. Until a dead person appears who won’t go away.

Dream Image

Rafels at the wheel.

I fall into a restless sleep and get lost in a deep dream. I’m driving in the car, cheerfully bellowing along with the car radio. Ronny and Steven, a comic duo on Wednesday afternoon. Until something strikes me. I’m being followed. I’m instantly wide awake. The gray Citroën!

For weeks I’ve had the feeling I’m being followed by a gray Citroën, which I encounter in different parts of the city, and which repeatedly crosses my path by chance. In the evening when I come home, I can’t shake the feeling. Now I’m even dreaming about it. Am I getting paranoia?

For weeks I’ve had the feeling I’m being followed by a gray Citroën, which I encounter in different parts of the city, and which repeatedly crosses my path by chance. In the evening when I come home, I can’t shake the feeling. Now I’m even dreaming about it. Am I getting paranoia?

I wake up after my late-evening nap on the sofa and feel a bit chilled. It’s past midnight. It’s cold and I’m alone. Ibrahim isn’t here. That’s strange. It’s unusual for him. At this time of evening he’s normally snoring, wrapped in a synthetic but brightly colored and warm bedspread.

He likes to sleep on the floor, always looking for his African roots, but now he’s nowhere to be found. I close the terrace door against the draft and I put on something warmer before beginning to write. I just don’t know about what. This is the beginning of my second life, my nocturnal existence. I start the computer device, hoping to get an email that will set me on the right track.

Writing frightens me. I can’t begin without the support of the necessary stimulants and other rituals. The computer hums, crackles and sputters, and it’s busy making a connection. Somewhere in the house a tap splashes a slow drip. Carambole is sleeping deeply on her sofa and Farouq is on a raiding party in the wardrobe. With that our two cats are introduced.

In the distance a fire engine siren sounds, because we live close to the fire station. It doesn’t disturb the domestic peace, we’re used to it already. I’m going to mess around nicely on the computer this evening, like every evening, despite the cold. I start by letting the incoming messages come in.

To be continued…

Recente bijdragen

Racism in opera – avoid clichés and commit to inclusiveness

Taking racial elements out of opera Reading time: 5 minutes. Avoiding racial stereotypes in opera requires a thoughtful approach. Directors may […]

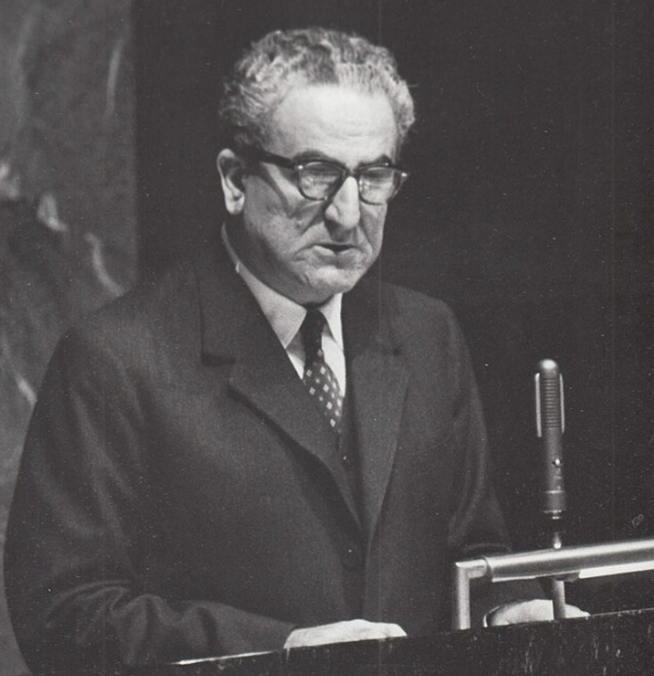

The UDHR – Charles Habib Malik’s ecumenical vision

Charles Habib Malik’s ecumenical vision Charles Habib Malik (1906-1987) was an influential Lebanese academic, diplomat, philosopher and […]

Back from the road – Florida

Florida Was Wonderful I don’t love America as a power, but I adore Americans. The way they interact with each other—we cold […]

No comments have been posted yet!