The morning consultation

I can start right away, several hours in a row until it’s empty. Every time you think, I’m almost there, someone else comes in. At a certain moment a lady goes outside, and there stands Louis Van Droogenbroeck, the neighborhood policeman, but in civilian clothes.

“Doctor I have to ask you something. You saved my life that day. You kept me there. Otherwise they would have taken me to the hospital. I’ll never come out of there alive, once I’m in. But may I ask you a question. I’m not really supposed to ask, but your Dutch friend?”

“Who’s that?”

“That Dutchman who’s often sitting in your waiting room.”

“What about him?”

“Could he have had something to do with that affair with that Ricky?”

“That’s a very serious person, Louis. And he’s a fine person. I hope you’re not going to speak ill of him.” He looks fairly serious. “Did you watch the Eurovision Song Contest, Louis?”

“Yes, Latvia won. A beautiful song. I was rather for that French one. Nice girl.”

“What can I do for you?”

“My back is giving out. I can’t take it anymore. I’m tired. I have constant pain. I have to take more painkillers.” He sits as stiff as a board on the consultation chair. He can’t take overtime and accumulated leave, because of demonstrations and football matches. The reorganization of the police services leads to uncertainty in the entire force. Then I think to myself as a general practitioner: “You have the back, but you also have everything else gnawing at you.”

You try to see the whole picture, not just the diseased organ. The complete Louis. He can’t go on. It’s beginning to look like a burn-out, or a depression, that’s also possible. Although burn-out and depression are two different things, the difference isn’t always easy to make. Louis has always loved his work dearly. Now a spring has broken in him.

What’s gotten into him? The successive police reforms, or is there more going on? This isn’t just simple back pain, I sense that with my general practitioner’s nose. He does of course have a very bad back. The file will show it. Repeatedly I’ve told him that with this back he could actually be declared disabled. That didn’t go down well. He insisted on continuing to work and specifically on the street, as a neighborhood policeman, rather than in an office.

“Walking is good for the back. I like being in contact with people.” I can go along with that. I can sense his nervous tension, even when he becomes somewhat secretive:

“There are many things that shun daylight. Things I’m not allowed to tell anyone.” Take now that Richard van Genechten who’s dead, that Ricky. I’ve been walking in this neighborhood for fifteen years. Every day some leave and others arrive. One of our tasks as neighborhood policeman is to go check whether people really live where they say they live, for example in case of address change. I usually find an assignment, with an address I have to visit in my pigeonhole.

In the case of Richard van Genechten it was different. I’m summoned by Mr. Robeyns, a type from the old judicial police, if you understand what I mean. He gives me the assignment personally to visit the location to conduct a residence investigation. He wants a secret report, which I’m to give him directly, and not pass on through the corps commander, as is customary. Robeyns doesn’t tell me what to look for. He looks at me grinning and starts licking a cigar.

“I want to be the only one, if not the first to know, if something happens with Ricky. You mustn’t take action against him, under any circumstances. If there’s anything, you call me, on my personal cell phone. You mustn’t use the number for anything else. Don’t talk to anyone about this.”

So much for Robeyns. Now I ask you, Doctor Rafels: “Why was that Richard Van Genechten so important? He was a junkie, damn it? Using drugs isn’t allowed, but like him there are hundreds who don’t stand out. I’ve been able to keep my neighborhood reasonably quiet for the past fifteen years.”

“We’re sitting here in the heart of Brussels five hundred meters from Little Chicago, and look at the shops with fashion and unique ladies’ hats in the window, or the optician’s shop with all those difficult glasses that each cost a fortune. Everyone is safe here, isn’t it? At least during the day when I’m there. What do they need their police reform for then?”

The stork

The restaurant where Rafels and Wiebe are having lunch is called La Cigogne.

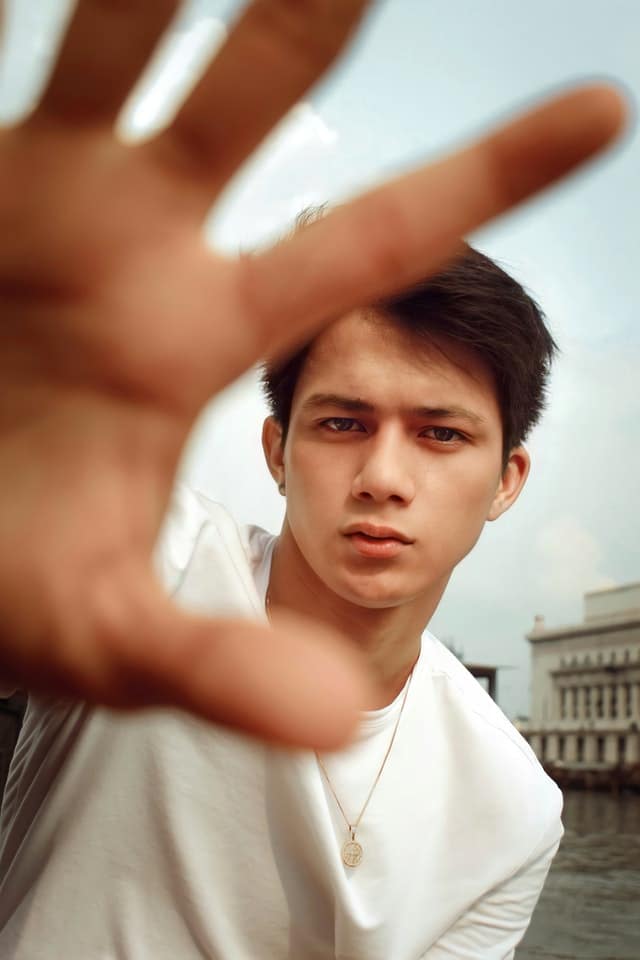

We see Ricky (and Wiebe) in the supermarket. Wiebe and Ricky take a taxi. Ricky in a café along the boulevard. Nervous snapshots, a bit blurry. Ricky does look photogenic in his sullen way, I must say. Not unattractive, a bony face, but still something soft. Sad. Nothing aggressive, rather naive. Unmistakably sexy.

“He looks straight into the lens, just as he knew how to look you straight in the eyes. They’re just snapshots, most made with disposable cameras.” Another photo shows Ricky in a t-shirt, but a bit flou artistique: thin, not yet really a full man, sharp nose, long limbs. Always a bit naked in all his clothes.

“For me he was a source of life, but in himself an orange dwarf, an old star about to collapse and giving off its last red light, an ancient soul in that young body. A missed opportunity. He was a boy who wasn’t allowed to be one, a man he didn’t become. I can’t believe he committed suicide. Then he would have talked to me about it, wouldn’t he? When people are going to commit suicide, they say something about it, don’t they?”

“Did you live together?”

“We spent a lot of time together during this short period. Not living together or anything, are you crazy. It probably didn’t last long enough for that. It was a more or less fixed regularity of going out together and then ending up in bed, usually mine. I’ve been to his place once, but there was no comfort to be found there. It was a squat he lived in, or that’s what it looked like anyway.

In bed we fit together very well. Those are the best memories I have. He had the key to my house for a while, but at a certain point I asked for it back, after something unpleasant happened, which has nothing to do with this.”

Wiebe looks much better now than several weeks ago. He’s calmer and more rested. The new pills for depression are starting to work well. He’s also starting to explore very different themes.

“The Eurovision Song Contest just happened. This time I sat watching next to his mother. I can’t help going back to thinking how we sat together, next to each other, Ricky and I, watching the Eurovision Song Contest that year. It was the year Israel won with a transsexual artist.

Ricky was crazy about Abba, despite his young age. It’s one of those little things you can get absorbed in. It’s unbelievable that another year has passed. Time goes fast, but some things always stay the same, like anger. Estonia has won now, with the help of a Dutchman from Aruba.

We’re increasingly separated from Ricky in time and space, though while watching the Eurovision Song Contest in Brigitte’s company, there was still the feeling that he was there. Every year despite myself I remain hypnotized for an hour watching the deadly boring announcing of the points. Finally the winner gets to sing again in an incredible atmosphere of confetti, artificial snow and fake sets.

I can’t manage to watch those stupid songs all evening anymore, but the points ceremony, followed by the finale, that’s the worst television ever made, and every year I remain captivated by it in spite of myself. There’s something exciting about so many people in all of Europe and beyond staring at absolute nothingness.

The show business brought me to yet another idea. I thought back to a figure from Ricky’s circle whom I’d somewhat forgotten. I found a photo of him in my growing collection of paraphernalia. A photo of Ricky with Fernando in a transvestite bar. I now also remember that Ricky at the time, when Israel won, called this Fernando to share in the joy.

There had once been a brief relationship between them, but it hadn’t lasted. That was before my time. However, Ricky and Fernando always kept in touch, and that happened in an unhealthy atmosphere of drug use and secret schemes. That’s why I never wanted to meet that Fernando. I said nothing about it.

Now that man also resurfaces, photo and all. I’ve spoken about it with Brigitte. We think we should do something, to learn more about the dark side of the matter. We’d like to talk with Fernando. And also with the boy we saw at the time of the cremation.

According to Brigitte, that can only be Abdelhak. Ricky talked about him in prison. He shows up in the story at the end of Ricky’s life. That’s how we came up with the idea of looking for these guys, where they are, especially in the gay milieu, or do you know of a better way to get in touch with them?”

“My dear Wiebe, I am the first to admit my ignorance.”

“Fernando has yet to be a variety artist, in the travesty scene. Abdelhak is more in the direction of skating and rapping.”

The kitchen table

Rafels sees it coming already

“Doctor Rafels, will you come with us and help search the Brussels gay scene for this Fernando and this Abdelhak?”

“Have you completely lost your mind?” I get a slight flush, despite myself, like every time someone points out my orientation. I’m momentarily speechless. “Surely you know your way around there better than I do? I haven’t gone out for years. I probably wouldn’t find anything. I’ve stayed away for more than ten years. What do I have to look for in the gay scene now? At my age? I’m turning forty-five. I’m married, divorced, I live with a steady boyfriend. I have a child, pardon, I should say children. No, no, I have my comforts at home, let’s say.”

“Oh you’re a nice man. You know a lot and you surely know many more people in Brussels than Brigitte and I together. The good woman is determined to dive into the gay scene. I can’t let her go alone, and two gentlemen for a lady seems more appropriate to me than accompanying her alone. You can set us on the right path, two know more than one.”

I’m not comfortable with this. I get a feeling I’m being dragged into something I can’t oversee. When will I still find time for my family? I clearly don’t know what I’m starting. I returned somewhat worried to the practice.

During the evening consultation at an opportune moment a middle-aged woman with a hat, a raincoat and a large bag comes in. She introduces herself as Brigitte. “You know, Ricky’s mother.”

“What a surprise!” She’s heard much good from Wiebe about my services as a general practitioner. Now that she’s in Belgium for some time due to unforeseen circumstances, she needs her pills, her follow-up treatment.

“My uterus was surgically removed three years ago. There was cancer in it, but it hasn’t come back. I do have to keep taking pills. The treatment wasn’t finished yet when I heard that Ricky was dead. My child was dead and I knew I wouldn’t have any more children.”

Then something is literally and figuratively cut out of you. In more ways than one. The idea of ever wanting another child has never left Brigitte. The next moment all that is gone. It’s no longer possible.

“I kept doubting, until all doubts were removed. I just can’t get over it. I don’t know what keeps me upright. Perhaps the feeling that there’s still something I don’t know, something I’d very much like to know. I want to understand so I can accept.”

“What image do you retain of Ricky?”

“I still see him as we sat there, while we drank coffee together at the kitchen table, that time he came to visit me in France, sullen and fairly melancholic.”

Bad news

What Brigitte didn’t yet know is what he’d been up to.

What I do already know is that I’ll be operated on. We drink coffee at the little kitchen table. He avoids my gaze. I’m too overcome by my own grief and fear to investigate further.

We’ve become estranged from each other. It started when he went to boarding school, under Caroline’s pressure. Or was it earlier? No father to pick him up from school. Despite everything it’s a conservative country, certainly in the provinces. Ricky has always been a strange duck. I suspected it very early on. A mother knows that. There are signs that don’t deceive.

At this same kitchen table he once told me he was for boys. It was never a reason to be angry with him, or not want to understand him. Homosexuality isn’t bad, compared to the realization that he made nothing of himself. Ricky couldn’t do it. He found that terrible himself. He failed at everything. The biggest shock was when I discovered he was using drugs. That was the beginning of the end.

I couldn’t have thought that this person, who was born from me, would ever fall apart, overtaken by death, just at a moment when I myself was saved from cancer, by skilled surgical hands. Ricky always had something sad about him. When he played harmonica, you became very melancholic.

As if he wanted to ask: “Mother, why did you bring me into the world?”

He became considerably more cheerful when he met Wiebe. The “Flying Dutchman” helped him put things back in the right perspective. Under Wiebe’s influence Ricky opened up a bit. He brightened up. He told me everything that year. It was about the only episode in his life when we had much contact. It went up and down like that.

One fine day the bad news comes out, while we were drinking coffee at the kitchen table again. Not yet the whole truth. He said nothing at the last kitchen table about his troubles with the law. He did confess that he’d botched all his study opportunities. Didn’t get through a single first year, although he tried three directions. He never made it to the final exams. He just kept pretending. He lied when necessary and acted as if he’d passed. He managed to keep that up for two years.

Now the secret broke through like an abscess. “And your future. How do you think you’ll earn a living?” He does a number of unclear things, “odd jobs for the police” he says with a grin. “Maintaining order.” He clams up, says nothing more. He doesn’t want to tell what’s really wrong with him. The moment is over. He leaves for Brussels again. The following days I can’t make contact.

I call the landlord and he informs me that my son is in jail. I had to lie down for a moment when I heard it. Drugs. Prison. He hadn’t dared to tell me he was in this kind of trouble. I traveled to Brussels immediately, but couldn’t stay long. I had to go back for my treatment.

At first I didn’t even have the right to see him, because he was placed in isolation. Garde à vue. I arranged a lawyer and advocated for good medical care. He needed it given his drug history. He was released after a few weeks. He himself undertook nothing to defend himself. He acted indifferent, sick with longing for drugs as I thought then, or was it broken resistance, as I think now?

“Doctor Rafels will you help us search?”

To be continued…

Recente bijdragen

Racism in opera – avoid clichés and commit to inclusiveness

Taking racial elements out of opera Reading time: 5 minutes. Avoiding racial stereotypes in opera requires a thoughtful approach. Directors may […]

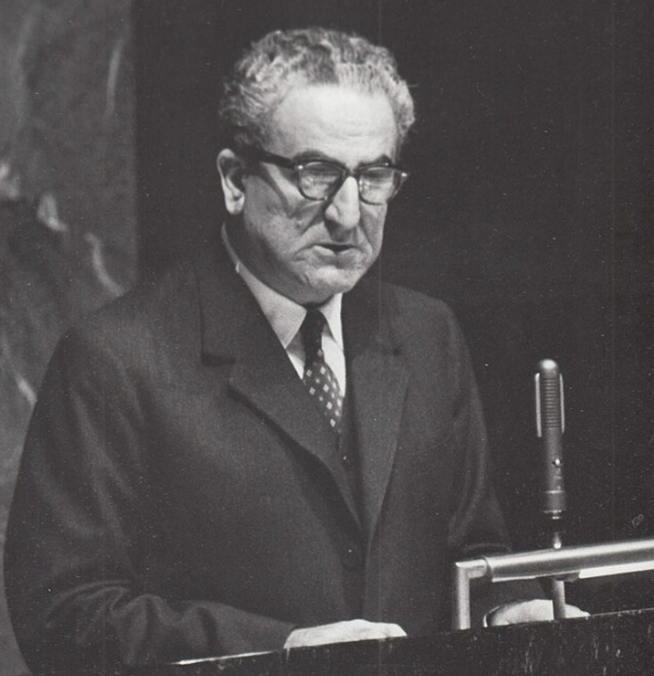

The UDHR – Charles Habib Malik’s ecumenical vision

Charles Habib Malik’s ecumenical vision Charles Habib Malik (1906-1987) was an influential Lebanese academic, diplomat, philosopher and […]

Back from the road – Florida

Florida Was Wonderful I don’t love America as a power, but I adore Americans. The way they interact with each other—we cold […]

No comments have been posted yet!