It is a wondrous setting for the kick-off meeting: Brigitte, Wiebe and Rafels.

It’s rather like Erwin and the detective club. It had been somewhat my demand, if I had to go along with Wiebe and Brigitte to the Brussels gay bars after all, that we would meet here in the Falstaff, so as not to go into the night without first having enjoyed a good meal.

Together we choose Flemish carbonnade, what we used to call stew at home in Flanders: a stew of originally second-class beef, now first-class in a dark brown lightly caramelized sauce based on fried onions.

It’s pleasant chatting. There isn’t a minute of silence while we’re waiting for the meal, playing with a piece of bread and some butter and an aperitif. Wiebe and Brigitte talk the whole time about just one subject that’s slowly beginning to show obsessive characteristics: the life, works and death of Ricky.

Wiebe has just finished his interrogation. “It went reasonably well. I was received by Mr. Robeyns, in the annex of the Palace of Justice on Vierarmenstraat.” He’s a courteous man, but still asks cutting questions.

“How and why did you give Ricky money?”

“Ricky and I lived just around the corner from each other at the time. Ricky had a telephone, but no connection. He was in acute financial distress. The unpaid bills were piling up. He had just gotten out of prison. He was having a hard time. I lent him money a few times, because he was completely broke toward the end. On the other hand, I also turned him away at the door a few times when he was drunk, but that didn’t help. He kept coming back. We lived on tense footing.”

“Did you have a heated argument about something?”

“No, not that either.” The detective hands me a stack of photocopies and asks if I recognize anything. “Those notes were on Ricky’s cupboard when he was found dead.” I recognize my handwriting immediately. Since there are a few on letterhead with my heading on it, I could hardly deny it. I can hardly deny that I had a relationship with him.

“Where were you at the time of death?”

“I think I have an ironclad alibi. I wasn’t in the country when he died, as I could easily prove, based on my diary. I was in Strasbourg that week for a session of the European Parliament.”

“What did you last eat that night before you left?”

“I don’t remember.”

“Was it something Italian?”

“I cook Italian, when I cook, yes, that may well be.”

At the end of the conversation, things got weird. After all, he became fairly emphatic: “Something with pesto?”

“Yes delicious!” I mumble something. Then it’s apparently over:

“Dear Mr. De Vries, you will probably be pleased to know that we can soon close this unpleasant matter. You would prefer that everything we discussed here remains strictly confidential, wouldn’t you?” While saying this, Robeyns looks at me meaningfully. “Isn’t it better if it’s never spoken of again? At a certain point the matter must rest, so that the wounded heart can heal.”

I left with the feeling that he couldn’t or wouldn’t answer any of my questions, and that he elicited some answers from me that I’m not so sure about anymore.

We don’t know the answers to many questions. We know for certain that Ricky’s death was not a natural death. We know the circumstances in which he was found. We don’t yet know what the judicial investigation has brought to light, but we can find out, thanks to the Franchimont law. Brigitte can gain access to the investigation files, because as a mother she can file as a civil party. “I can’t do that myself. I’m not a family member. I was only his small-time lover.”

Brigitte

Wiebe: Legally that gives me no status whatsoever.

“The body was released after a post-mortem examination. The autopsy report must be in the file. I’d like to read that.”

Brigitte interrupted:

“They didn’t let me see him. I really wanted to see for myself what was left. But that wasn’t allowed. I still regret that. It was expressly forbidden by the judge. What was left of him to cremate, after the autopsy? I often think about that.”

“If it wasn’t a natural death, what was it then?”

“Then it’s either murder, or suicide, or an accident. An overdose for example. Something too strong. It doesn’t always fit into a box.”

“Even if it was an accident, you can still try to figure out why it had to happen that way. You can learn from that. However, if it’s murder, then there’s one more thing: the unmasking and punishment of the perpetrator.”

“Well, let’s assume for a moment that it was murder. Then who was the murderer?”

Brigitte picks up on this, with a little too much eagerness: “Why not his father? Or his father’s family? The Van Genechten family.” She seems to be getting a little drunk.

“What kind of people are they?”

“Caroline Van Genechten has three sons. The eldest, Albert, has led the glass business that forms the basis of the family fortune since the death of the prematurely deceased father Kamiel.

The second, Bernard, is a lawyer and politician and has made it to minister. Brussels Minister of Agriculture. There’s no agriculture at all in the Brussels government.”

“There had to be a Flemish there.”

“The third, Victor, is the pilot. Victor is quite a bit younger than the other two. I dare not say it about Victor, but I know for certain that the brothers hated the idea that there was a Ricky van Genechten walking around somewhere. They are responsible for his feelings of being neglected. They’re selfish brutes, every one of them. They could have helped Ricky, but they didn’t.”

It becomes too much for Brigitte and Wiebe and I sit watching. Her face falls apart and her makeup runs. Brigitte resumes sobbing: “I called them all, all the Van Genechtens, when Ricky was in prison, hoping someone would intervene. They were unreachable or not interested. I wrote to them.”

Albert was hermetically sealed off by a sharp secretary. Bernard threatened legal action. Caroline was the only one who spoke to Brigitte on the phone. “That’s how I found out that she stopped depositing Ricky’s maintenance money when she knew his studies had derailed.

Ricky never told me this. Neither did Caroline.”

The money came into Ricky’s account in Brussels, and then it suddenly stopped without warning. According to Caroline, he was now an adult and should stand on his own two feet, since he was no longer studying, as had been contractually agreed.

Caroline alone possesses more than half of the immense family fortune. She is like a spider in a web with threads of money. Though you can’t deny that Caroline still meant well somewhere, compared to the sons.

For my poor Ricky it can no longer help. It wasn’t that he wasn’t intelligent. He spoke Dutch and French well, but had difficulty writing them. He wasn’t very academic. The back and forth switching between the French and Flemish school systems probably didn’t help either. He was primarily a boy who couldn’t find a place in society.”

Boulevard

A café full of men and a single woman

For my poor Ricky it can no longer help. It wasn’t that he wasn’t intelligent. He spoke Dutch and French well, but had difficulty writing them. He wasn’t very academic. The back and forth switching between the French and Flemish school systems probably didn’t help either. He was primarily a boy who couldn’t find a place in society.”

It’s a corner café with a rounded facade. The bar is also round and takes up three-quarters of a circle, with the same center point as the curve of the facade. Someone really thought about that, in my opinion. The circle of the facade is set within a right angle of walls. You’d have to see it on the plan.

Behind the bar, a hyperkinetic man in his mid-fifties is serving, under fast hit music, assisted by two agile Maghrebi lads in jeans and t-shirts.

All the stools and tables in the bar are overcrowded, with an almost homogeneous male audience, of the tough queen type and from diverse ethnic groups.

Yugoslavs, Moroccans, Russians, Turks. It creates an underlying tension, though you don’t notice any conflicts, perhaps because no one forms a majority.

The music is loud, but not so hard that you can’t talk. Our company attracts little attention until the boss loudly calls out while changing the music: “Hey mister doctor.”

I involuntarily cringe, because I always feel that mentioning my title in this environment is better avoided, for some reason.

However, it’s meant warmly. I go to shake his hand. He wants to kiss. It leads to a little chat. We know each other, because he’s one of my patients. He briefly updates me on his health condition while taking time to light a cigarette. I order: “Give me a Palm, ask those two people what they want, and have something yourself too, André.”

He pours himself a drink and sends a waiter to my two friends to take the order. I decide to take the bull by the horns and ask if he knows Fernando. “Fernando?” André scratches his sparse hair. “Fernando. That’s a Brazilian from Aarschot and he performs in the Capriccio, I believe, if he hasn’t left. He was such a fantastic artist, in the past, that Fernando.” André shows with a raised thumb how fantastic.

“Such an artist, but he has fallen on hard times a bit. He’s lucky he still found a little job, in the Capriccio, because the better establishments don’t want him anymore. They say he’s on drugs.”

“What does he do?”

“Still the good old stuff, surely? Shirley Bassey. Nothing more recent than Abba. He was a fine artist, really. He did a brilliant Dalida in Paradisco, with five dancers and two Afghan hounds for his entrance. There’s not much left of it. La vie de star.” La vie de star.”

“Ce n’est pas évident. And Abdelhak, does that name mean anything to you?”

“I think so, but I’m not sure. A handsome guy? A little Moroccan? I still look at them with much pleasure. They like to give themselves another name, you should know. Abdelhak is probably called something else here. Olivier or something, they like to hear that, or Alexandre. Hairdresser names. Cédric. Igor. Or something English: a Karim who becomes Charly for example.”

“Have you ever known a Ricky van Genechten?”

“Bad news Ricky or Ricky Catastrophe. Yes but that was years ago. They say he’s dead.”

“Have you ever seen Ricky and Abdelhak together?”

“Yes, but what you’re asking me now. It’s more than two years since Ricky died. What you’re coming up with now. Abdelhak doesn’t come so often, if that’s the one you need. He sometimes sits down the street. In the Incognito. You can always walk by there on your way to the Capriccio. The show doesn’t start there until half past one tonight anyway.”

“Would you please not tell anyone we talked about this?”

Wiebe and Brigitte have been able to secure two adjacent stools and are in conversation with each other. I arrive with fresh information about Fernando and Abdelhak.

“That Incognito, what kind of place is that?”

“That’s very very gay, Brigitte. Are you sure you can handle it? It’s even more homosexual than here. It’s a private club.”

“I find gays terribly nice. I feel very comfortable here, among all these men. Of course I’d like to go to the Incognito, if they let me in. We have to at least try.”

Indeed, Brigitte seems to integrate wonderfully into this nocturnal world. As the evening progresses, she talks to one gay man after another, with the greatest ease in the world. I can only be envious of it.

Incognito

Wiebe thinks it’s just narrow, hot and loud.

The packed Incognito takes place in a narrow ground floor of an old townhouse that’s been transformed into a gay bar. It’s crammed full of exuberant queens and faggots. The ‘ambiance’ is present. We have to squeeze our way in. The men stand shoulder to shoulder, belly to back, dancing in place to the music. However, we manage to squeeze through and discover a small spot at the back where we can stand and breathe.

The music is cheerful and extremely loud and talking here has to be done by shouting. Brigitte looks around bravely and actually strikes up a conversation with a boy I would have liked to talk to as well. I see the boy shake his head no. She’s already approached a few people this evening, people she doesn’t know from Adam, just on instinct, each time with the question do you know a Ricky, do you know a Fernando, do you know an Abdelhak.

It amazes me, and, frankly, it gets on my nerves a little. I don’t know why.

I’m usually quite shy in this kind of place. The boss comes over to us and we start talking. Business is good and he’s reasonably cheerful. He’s probably had a drink or two. Before anyone gets a chance to ask the main question, he starts talking about it himself. “May I tell you something? What you’re doing, you’d better not. Asking questions about Ricky, Fernando and Abdelhak and that sort of boys.”

“How do you know we’re doing that?”

“That doesn’t matter. You better not do it so conspicuously. I’m telling you as a favor to you.”

“Do you know those boys then?”

“Let me put it this way. The idea that three unusual customers are walking around in the evening asking questions about those boys might give some people ideas. I’m not saying more.”

“Yes but what do you mean? Tell me!”

“No, that’s all I have to say about this. It’s dodgy business and I know nothing. I’m saying nothing. Would you like to have a drink on me? But only if you stop asking questions.”

“I know this landlord,” says Rafels, when he’s gone. “I’ve known him for years and have never caught him doing anything wrong. Not someone who talks nonsense, in principle.”

Suddenly the hyped-up carnival atmosphere of this place strikes us, and we feel watched. It doesn’t take long before we’re outside in the little street. We haven’t found Abdelhak, but we still have the possibility of meeting Fernando in the Capriccio, but only after half past one at night, as we learned from André, so we have some time to kill.

The really very extremely gay places, with moist caves and such, we decide not to do with Brigitte along for a first time. We let this cup pass us by.

We therefore decide to return to the corner café on the Boulevard. The same café is not as full as before. There’s even a table free. All hell has broken loose in the person of an unchained André with a shiny little hat, who loudly spouts frivolous nonsense and sings along with the music: oriental sounds, what you could probably describe as Arabic rock.

The Moroccan boys join in cheerfully and now and then one ventures a few dance steps, never more than one at a time. A black boy dances with a beer glass on his head under loud and rhythmic cheers. André comes to his senses sufficiently to tell us a bit later that Abdelhak was here this same evening.

André knows for sure it was Abdelhak, because he immediately took off when he heard that a lady and two gentlemen were making inquiries, so it must have been him.

“Apparently we’re not using the right method to find Ricky’s friends,” Brigitte dryly remarks over a hot Belgian coffee, with a chocolate that she carefully unwraps.

To be continued…

Recente bijdragen

Racism in opera – avoid clichés and commit to inclusiveness

Taking racial elements out of opera Reading time: 5 minutes. Avoiding racial stereotypes in opera requires a thoughtful approach. Directors may […]

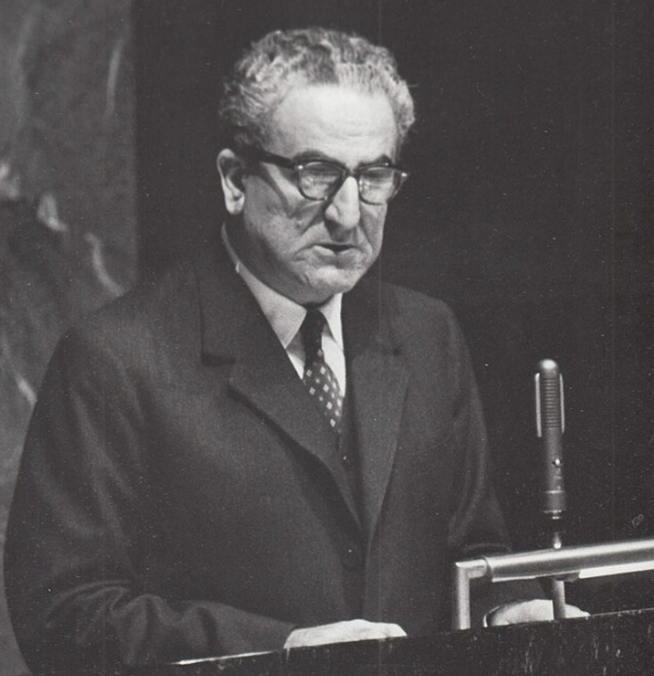

The UDHR – Charles Habib Malik’s ecumenical vision

Charles Habib Malik’s ecumenical vision Charles Habib Malik (1906-1987) was an influential Lebanese academic, diplomat, philosopher and […]

Back from the road – Florida

Florida Was Wonderful I don’t love America as a power, but I adore Americans. The way they interact with each other—we cold […]

No comments have been posted yet!