Reconstruction

Brussels 1998, Charles Baudelaire Street.

Close-up of Louis Van Droogenbroeck in uniform: “In my capacity as neighborhood officer, I proceeded that morning to the given address, where I was ordered to go, at Rue Charles Baudelaire Street number 26, fourth floor right, in the municipality of Brussels, in order to investigate a suspicious disappearance.

The building comes into view. It hasn’t changed. It’s an old rental building let out by floor in a not-too-great street. Louis’s voice continues: “The tenant’s name is Richard Van Genechten. He hasn’t been seen since the end of last week.”

It’s an ordinary Brussels June morning, with cars in the damp streets, after a spring shower. Around 9:30 a.m., Louis rings the bell. A concierge opens the door, a faded woman in a pink dressing gown with curlers in her sparse hair. Louis goes inside. She speaks French from a not entirely toothless mouth. Together they climb the narrow stairs to the third floor.

Halfway up the stairs, she turns around. “Do you smell it too?” There’s a sickly sweet smell hanging in the air, faint but stubbornly drifting in wisps. Now you smell it, then you don’t. A smell of dog food?

“Une sale odeur. Vous savez.” Hand to her throat. And then she makes another gesture, as if plunging a needle into her arm. She rounds it off with a suggestive wink. Louis knocks and rings and identifies himself loudly as the Local Police. No one opens up.

They go downstairs to telephone from the concierge’s underground dwelling. The officer calls the duty officer at the station, who orders him to wait until a locksmith arrives. “Should the federal come to the scene? What’s the seriousness of the situation?”

“No, it’s probably another overdose.” Floral wallpaper in the stairwell. A torn poster from Verona from the eighties. They go back upstairs. The concierge opens the landing window with great difficulty to get more air. The locksmith comes stumbling up the stairs. Opening the locks takes little time.

“We’re lucky. No bolts, no security locks, no key in the lock on the other side.” The locksmith takes a step to the side so the door can be opened.

Louis looks cautiously around the doorframe inside, while the woman makes herself scarce, waiting one floor down for what follows. In the room it’s a mess: a filthy carpet, worn-out furniture, worn shoes, dated posters. The gaze slides further inside.

An orange crate on four beer cans serves as a coffee table. The top is covered with junk, including an empty pizza box, an open bottle of champagne in a bucket, two different glasses, and a harmonica.

A sickly sweet putrid smell overpowers everything, causing the neighborhood officer reflexively to bring his hand to his mouth. There’s still vaguely an undertone of stale cigarette butts and half-decayed food and drink remains, supported by flourishing mold species, but what dominates is the unmistakable stench of the rotting corpse sitting there collapsed in the two-seater behind the coffee table.

The dead young man is dressed in jeans and a T-shirt. His face shows sunken eye sockets, the empty gaze directed at the full ashtray, in a smellable state of decomposition, but still very recognizable. The television is on the local channel in an endless loop. Silly presenters, cheesy message, questionable hairstyles.

Louis wants to go inside to press the off button on the set, but it becomes too much for him. He becomes unwell, which first expresses itself in retching. He still manages to reach the landing, where he collapses from nausea. He thinks his last hour has come and lies groaning. The concierge makes herself scarce and runs down the stairs. The locksmith, however, is good enough to call the emergency services via his personal mobile phone. “We’ve got a dead citizen and a sick officer here! He’s lying here groaning.”

Rafels

A family doctor passes by unsuspectingly.

The concierge runs outside with curlers on her head tied under a pink scarf, her shapeless body wrapped in a pink glossy artificial silk dressing gown. She takes a sharp turn and almost collides with Doctor Rafels on the sidewalk. “Au secours, Docteur. You’ve been sent by God.” She grabs him by his sleeve and pulls him along inside, with such a jerk that his doctor’s bag in his other hand floats behind him.

“Docteur, docteur, c’est la catastrophe.” The local family doctor climbs the stairs breathlessly, and on the fourth floor, quite panting, encounters a fallen neighborhood officer, flailing on the landing. Louis Van Droogenbroeck points hysterically rattling, on the verge of fainting, toward the open door. The family doctor takes Louis’s pulse and quickly determines that he, although still very pale, is alive and kicking.

Feeling clammy and damp, he may have suffered vagal syncope, since heart rate, breathing and blood pressure are satisfactory. “Don’t think about me, doctor. Go look over there.” Once again the corpse comes into view: the remains of someone who is unmistakably dead, and has been for quite some time. Here any attempt at help comes too late. Only the official determination of death still needs to happen. You can see that from a distance.

You couldn’t be more dead. The gaze falls on the coffee table where a used syringe lies next to a spoon. Rafels keeps it as brief as possible, so as not to disturb anything in the environment.

He sprays his hands with alcohol from his bag, because he doesn’t dare touch anything and certainly not seek out the bathroom to wash his hands. He returns a bit sheepishly to the landing and squats down by the seated man.

“How do you feel now?” “I’m a little embarrassed.” “May I take your blood pressure for a moment?” From physical contact, the patient becomes calmer, at least if you yourself exude calmness.

The locksmith makes himself scarce. “This is getting too risky for me. I’ll send the bill.”

We now hear the sirens of the local Brussels police. Wailing sirens, getting closer and closer until they storm up the stairs with drawn weapons. A bunch of officers fills the stairwell with muscle power and testosterone. They’re quite agitated, with bloodshot eyes. Over the service radio they heard, incorrectly, that a colleague was injured during the performance of his duties.

The discussion runs high. “Watch out for those drug gangs. They’re all infected with AIDS and Hepatitis!” Fortunately, no one fires their service pistol in the excitement. Louis has meanwhile fully regained consciousness. He wants to stand up. “Just stay seated,” says the officer. “Are you the injured officer?” “I’m not injured. I became unwell. We found a dead citizen.”

Well, that’s a relief. The officer calms his men down. “Where’s the body? Did you go inside? Are you sure none of the perpetrators are still inside?” The family doctor decides to intervene. “Allow me, Mr. Police Officer, to introduce myself. Dr. Rafels, pleased to meet you. It seems unlikely that those perpetrators would sit next to the corpse for several days.”

“How do you know he’s been dead that long?”

“I’m a doctor you should know. And you? May I know who you are?”

“Ah bon?” He’s clearly not impressed.

Ambulance

With wailing sirens, the flying squad from St. Thomas Hospital comes driving up. The bright yellow contraption parks itself among the police cars on a remaining corner of the sidewalk and vomits its human contents out of four doors simultaneously. The creative solutions to parking problems soon lead to the entire street being blocked.

About four people, dressed in orange fluorescent jackets, storm with full force into the groaning old house to care for the injured. They soon discover that this is only about a no-longer-resuscitable unknown person, and a meanwhile very lively neighborhood officer Louis Van Droogenbroeck, who is loudly giving his opinion.

The onslaught of urgent responders who arrive gets stuck in considerable congestion on the stairs and on the landings of the old building, where the police have already taken position. With a few words and gestures, everyone comes to false calm, after which the emergency doctor struggles up through the police cordon. She tries to get an overview.

In her wake follows a nurse with a case and an ambulance worker with an oxygen mask. They pay little or no attention to the deceased but throw themselves with all the more dedication onto Louis. He resists loudly: “Doctor Rafels, do something. These people want to take me away. I don’t need to go to the hospital at all.” A nurse puts scissors to his uniform sleeve and cuts through shirt and jacket simultaneously. Then she looks for a vein.

Rafels taps the colleague on the shoulder and tries to explain: “The neighborhood officer has recovered from a fainting spell, due to the stench, the heat, and the emotion. He feels fine now. He’s my patient, you should know. I’m his family doctor.” The head of the emergency team, a sturdy woman with glasses and a mustache, reluctantly admits that Louis is in good health and has probably experienced a syncope. Blood pressure is good, heart rhythm stable, ECG satisfactory.

She gives up, but she can’t leave anymore. She’s stuck because more people have arrived. Meanwhile, doors have opened here and there, and the residents come to verify the cause of all the commotion. Some try to leave the building. It leads to a Jacob’s ladder of people present with different intentions, one wanting to go up, the other down, while the police officers just stand still.

Standstill

We’re all stuck together in the whirlwind of a human rush, in the eye of which is a corpse. Every movement leads to more standstill under considerable pressure. The wooden staircase creaks from it. Everyone climbs through each other a bit, without making progress. The cases with needles and ampoules of the departing emergency brigade are passed hand to hand over people’s heads. Half of those present are busy calling on their mobile phones.

Outside, the entire street is blocked by incoming intervention vehicles that can no longer leave..

In this election year, the mayor is also part of it in a car with a red-green flag. Moreover, an armada of the federal police comes driving up. On the street, the curious must be kept at a distance. The entire stretch of Charles Baudelaire is cordoned off because an injured officer was mistakenly reported. A helicopter flies over. The police receive telephone instructions that no one may leave the building until a high-ranking company arrives.

Mr. Gaston Robeyns, an inspector of the federal police, and Mrs. Monique Delamenotte, deputy to the King’s Prosecutor, don’t keep us waiting long. The street is cleared. The local police begin directing traffic. The disaster plan has been announced. As the emergency vehicles leave, the reporters arrive.

Everyone may leave after identity check and preliminary questioning. On television, Mrs. Delamenotte manages to give a reassuring account on the evening news. In the nightly news repeats, you can see over and over how a modest casket is carried outside and loaded into a long gray station wagon, in a cordoned-off and almost empty street, except for a police van.

To be continued…

Recente bijdragen

Racism in opera – avoid clichés and commit to inclusiveness

Taking racial elements out of opera Reading time: 5 minutes. Avoiding racial stereotypes in opera requires a thoughtful approach. Directors may […]

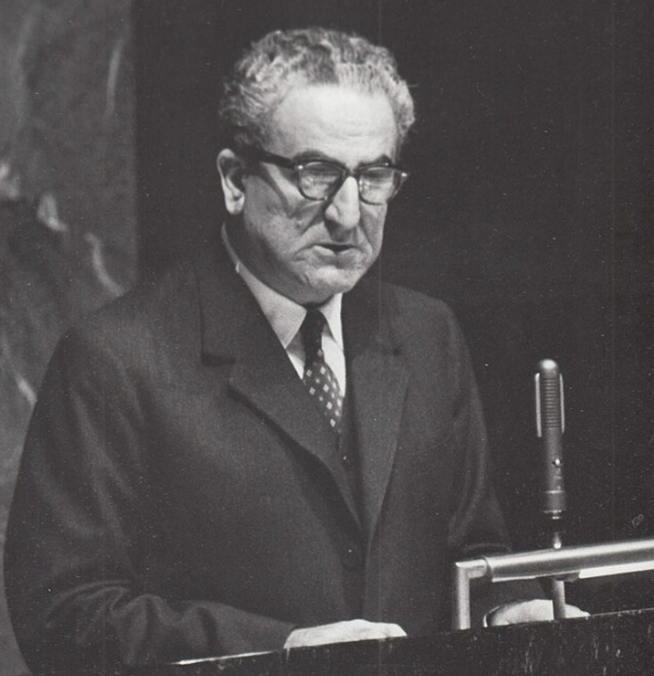

The UDHR – Charles Habib Malik’s ecumenical vision

Charles Habib Malik’s ecumenical vision Charles Habib Malik (1906-1987) was an influential Lebanese academic, diplomat, philosopher and […]

Back from the road – Florida

Florida Was Wonderful I don’t love America as a power, but I adore Americans. The way they interact with each other—we cold […]

No comments have been posted yet!