Ash scattering

On the spreading field.

An old liveried servant walks around with an upturned censer, from which the ash comes streaming out. The Islamic boy with the close-cropped neck has meanwhile disappeared. The rain takes possession of the dry dust and there’s nothing to be gathered here. Ricky has now dissolved.

The cemetery lies on a slope and offers a majestic view of the valley, beneath a wild cloud cover that turns black and gives rise to fresh rain. The gaze descends over gravestones gleaming with moisture, then creeps back up the incline, over the parceled landscape on the other side of the valley. Over there in the distance, sodden in the rain, rows of willows, hedges, arable land.

I feel strangely disappointed. Cremation speaks to reason, but not to the imagination. What has become of the eternal life of before? Is it over? After the scattering there’s no grave you can visit, though it must be said that graves are visited less than they used to be anyway. A pity that Ricky has no grave. Who wants to return to the crematorium to think of their beloved, where brown clouds belched fresh corpses into diesel smoke?

While we stand waiting for better weather, and because there are no other attendees at the funeral, I decide to strike up a conversation with this woman. I must immediately summon my best French, for Brigitte is French.

She’s come from Nantes specially for the funeral, or rather for the cremation. She finds it terrible how that ceremony went. She takes off her rain-spattered glasses and turns out to have surprising eyes. She looks much more appropriate that way.

Unexpectedly she reveals herself to be a lively, though affected woman. After three minutes we’re chatting away as if we’ve always known each other. I can’t understand everything she says in her rapid French, but I can follow most of it.

She’s come all the way from Nantes and she’s had to close her shop to be here, because she’s a saleswoman, in her own boutique rather than a shop. She deals in crystals and semi-precious stones.

The feeling that Ricky is nearby comes on strong, while I talk with her. I feel the same as at the beginning of our acquaintance and some of the good moments after: an immense curiosity, a churning stomach, and slightly on edge. Excitement. The same feeling he always knew so well how to evoke.

Inevitably, she also asks me, “How did you know him?”

“We were good friends. Je viens de Hollande. Il jouait très bien de l’harmonica. L’accordéon de la bouche. C’était un garçon très bon, au fond.”

Brigitte is apparently glad to be able to talk about him with someone: “Ricky told me about you, when he was still alive. He called you ‘The Flying Dutchman,’ perhaps because you fly around the world, in your capacity.”

“Mainly in Europe, I must say.” Brigitte smiles, looks at me and says: “Ricky was always searching for his father. He eventually ended up with you. It wasn’t such a bad choice, now that I see you. You have kind eyes. What star sign?”

I don’t engage with it. I can’t stand astrology. Did Ricky tell his mother we had a relationship? Did she know he was gay? She changes tone. “I myself can’t complain about Ricky. He worshipped me, but I couldn’t fill his emptiness. All the parenting books told me I had to let my son go and give him space. He went searching for things that didn’t suit me. I had to raise him largely alone, certainly in the early years, and I failed at it, so it appears.”

“Is his father still alive? I didn’t see anyone who looked like a father during the ceremony.”

“There wasn’t a single Van Genechten.”

“And that Maghrebi boy?”

“Must be Abdelhak, someone he mentioned occasionally toward the end of his life.”

Cookie box

Brigitte and Wiebe have kept in touch.

Once or twice a year we call each other to see if anything has happened. Brigitte has wanted to come to Brussels several times, but it never came to pass. The investigation quickly stalled, and there was never a good reason. So I wasn’t really surprised when she called me this evening. “Wiebe, c’est toi?” What was surprising was that she turned out to be in Brussels already. She came, she set down her suitcase in my hallway, and she stayed.

She looks robust, but not cheerful. Two deeper grooves between chin and lips say something about her moral strength and her determination. And yet she’s always to some extent upbeat and busy. She likes to chat, and at length. We sit talking nineteen to the dozen. It’s uncertain when she’ll leave again.

She has too many problems herself for that, because she’s a victim of flooding. The poor thing comes from a French town near the mouth of the Somme, which was completely inundated, as could be seen and followed on the French television channels. She’s lost everything, her house, her semi-precious stone shop, half a meter of water everywhere in the building. The whole neighborhood was evacuated and they were given coffee in a tent.

It’ll be a matter of reading tea leaves to know whether the insurance companies will pay anything back.

I enjoy occupying myself with deciphering from the French what she all means. I haven’t seen her since the funeral, or more precisely the ash scattering, until now. It must be going on four years. She hasn’t changed. It’s as if we’ve known each other our whole lives. She had the same hat on when she arrived as back then at the cemetery. It must be her traveling hat, in blue water-repellent fabric, with deep beneath the eye-shade: her piercing little eyes.

In her misery she found nothing better than to wash up in Brussels, where she hopes to find the truth about Ricky. On the mantelpiece she happened to have a summons from Belgium lying there when the flood came rushing in. Of all things, that paper, which had been lying there for two weeks, she just managed to stuff in her bag, with in her other hand a suitcase full of memories, when she was picked up by boat, along with the entire population of the flooded riverside district.

“I was uncertain whether to go to Brussels, but when the flood happened, I decided to leave hastily, to make the date for the interrogation.”

It could also have worked the other way, that she’d invoked the flood as a reason not to have to go to Brussels, but she didn’t do that. “As if I had to leave. It’s one of the necessary turns a life sometimes must take.” That’s what she says philosophically. Through the flood she’s lost much, but it has also freed her, says Brigitte. “I resolve, from now on to occupy myself only with the things that do matter.”

You can’t make out much from the summons. Nobody who wants to tell us what exactly it’s about. Given the circumstances I’ve offered her hospitality. For now she’s staying in my apartment, and I must say I feel unexpectedly good about it. She’s the only one with whom I can talk about Ricky. She cooks superbly and brightens up my bachelor existence with fresh things.

Review

Ricky seen through his mother’s eyes.

“He was a sensitive but pleasant child, who would do anything for me if I asked. The ideal son. He wanted to protect me. He was intelligent but often a bit somber. That was in him from an early age. He just wanted to be normal, not stand out, be spared attention.”

It went wrong from the moment he went to Belgium, to boarding school, against my wishes, but there was no other way.

He learned Dutch with extra language lessons.

Ricky was laughed at for his French accent and was probably deeply unhappy at the Flemish school in Brussels. It was a fatal mistake. “Perhaps that’s one of the reasons things went so badly later.”

Although his results remain below expectations, he still gets through secondary school, at the boarding school. It goes wrong in the first year at university. He loses a year to drinking, and probably drugs, and ends up on the fringes of society. “During holidays he visited me in France. He acted as if nothing was wrong, but I was worried. Sorry, it’s getting too much for me.”

“You’ll just have to tell this another time.”

“No, wait a moment. I’ve brought something else.” Brigitte has managed to save some of Ricky’s things. She collects herself. Photos from his youth, clippings, notes. A serious little fellow who becomes more beautiful as he grows up. And more tragic. There isn’t much left of his young life. It’s a flat biscuit tin from the seventies, but just the right dimensions so that A4-sized letters can fit in it.

She grabbed the box of things in haste and stuck it in her suitcase, next to figuratively speaking a pair of underwear and a toothbrush, when she was picked up from the floods in France.

She doesn’t show me everything. She examines each item thoroughly first, turns it over and then decides whether to show it to me or not. A few scribbled notes from the young Ricky from boarding school testify to little literary talent. No trace of feelings or original ideas in those short sentences, though you can gather from them that he misses his mother. There’s also a photo of Victor Van Genechten. A handsome man with a mustache in an aviation uniform.

“He’s an international pilot now, but he was at the beginning of his career then. Often away from home. Children weren’t in his life plans.” Her voice falters. When she talks about Ricky’s father, Brigitte quickly becomes vague and reticent.

We ate green beans with bacon tonight, which she prepared very nicely. “That they are summoning us now means there may be a trial after all. Your summons and mine, it can’t be a coincidence.”

“The face of the neighborhood policeman spoke volumes when I discussed it with him. Belgian justice follows inscrutable paths.”

“Ricky’s coming back to life a little bit, which is kind of crazy.” It gives me peace, knowing I’m not the only one still thinking about Ricky. I think she is a brave woman. We cry a lot, together.

This afternoon we went back together to the scattering meadow, at the cemetery in Uccle, on the same rickety little tram in unrelenting rainy weather. Magritte’s umbrellas, now open, then closed again, bob above humanity. The tram cuts remarkably straight through the winding rows of houses, beneath that strange aquarium light you get in this Belgian weather. It’s been raining for months now with intervals too short to let the city dry. The seeping moisture, you gradually go mad from it.

The fellow passengers look sullen and indifferent, because it’s so cold and wet for the season. As they dry, the tram travelers seem to congeal and stiffen, until they still spring to their feet when their stop comes. Everyone forms a planet of loneliness and no exchange between them. The chill moisture finds its way through the seams of our clothes, after our umbrella gives out under a gust of wind.

Scattering Meadow

There happens to be an ash scattering going on.

I’ve brought a video camera this time. While filming I had that same feeling again, that Ricky is here, somewhere close to me. It’s the same operetta figure with his censer, walking around scattering someone else’s ashes. If you watch the video later, it could be Ricky’s ash scattering. You can’t see the difference anyway. Nothing resembles ash like other ash.

The ceremony is completely rained out, as if you’re getting a wet dishcloth in the face, from the bitter wind, and filming becomes impossible. We catch our breath a bit, over a hot onion soup in the local tavern. Questions and doubts and regret. Then she starts talking about drugs. She doesn’t want to reveal much and it costs her effort to keep her emotions in check.

“Have you ever used drugs?” The question hits me amidships, but I answer truthfully: “I’ve never touched heroin or cocaine or other hard drugs. Admittedly, a few times a line of coke, in New York in the early eighties. It didn’t lead to habit formation, rather to disgust. I can’t bear the thought of drugs. A glass of port is much more pleasant, or a joint.”

“You’d better not mention that during the interrogation, I think.”

“I am not a drug user, but I take pills, to tell you the truth. Prescribed by the doctor.”

“What does heroin do to people?”

“I wouldn’t know. Heroin, I don’t like it. No, you’re completely loaded. It happened to me once. I still get sick from it. I see little creatures crawling on the wallpaper, really. As if I’m floating around in a persistent swarm of mosquitoes. I’ve never been so sick. Not that I threw up. I lay on a mattress groaning and felt awful.”

“What did Ricky find in it?”

“Found or sought? Everyone finds the same bitter dregs at the bottom of the cup, but we’re all searching for something different, or we imagine we are. Some of my best friends use drugs, others take pills. That’s their choice. You’re not responsible for another person.”

“But what do they seek in heroin?”

“It’s very diverse: numbing of soul pain, warding off consuming fear, oblivion for painful memories, performance doping, control over one’s own behavior, social skills. Weight loss. Suppression of sexuality. Disconnection from the outside world. Being calm. Inspiration. Expansion of consciousness.”

“You can achieve that by meditating, right?”

“Maybe they haven’t found another way in their lives.”

The feeling that Ricky is still there comes up again and again, because I had the same conversations with him.

Recente bijdragen

Racism in opera – avoid clichés and commit to inclusiveness

Taking racial elements out of opera Reading time: 5 minutes. Avoiding racial stereotypes in opera requires a thoughtful approach. Directors may […]

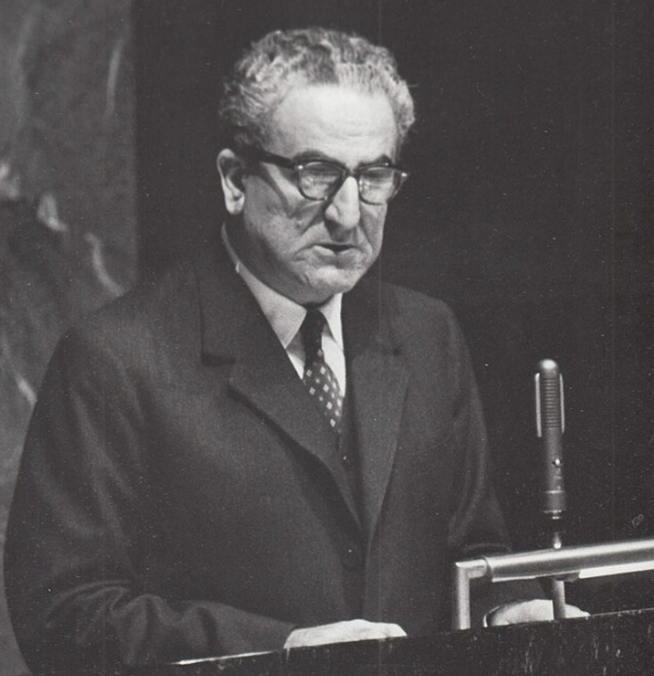

The UDHR – Charles Habib Malik’s ecumenical vision

Charles Habib Malik’s ecumenical vision Charles Habib Malik (1906-1987) was an influential Lebanese academic, diplomat, philosopher and […]

Back from the road – Florida

Florida Was Wonderful I don’t love America as a power, but I adore Americans. The way they interact with each other—we cold […]

No comments have been posted yet!