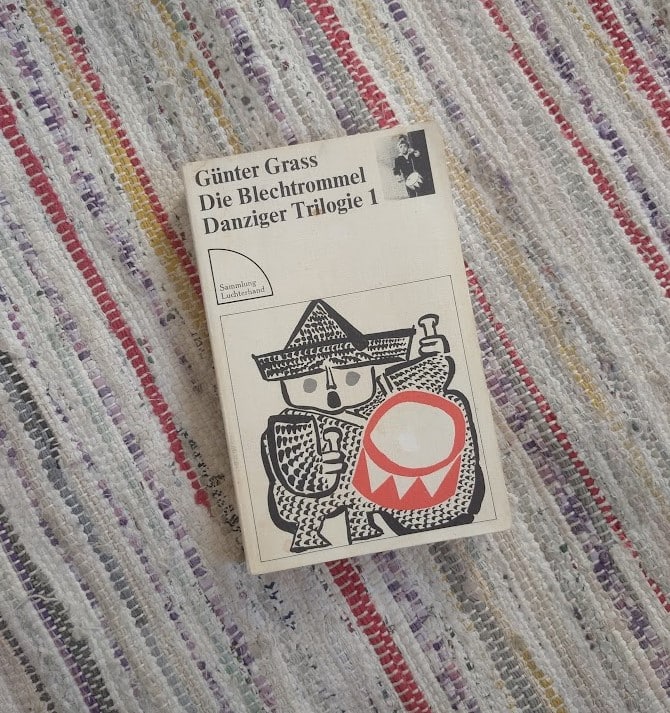

The Tin Drum / Die Blechtrommel

Allein auf Rasputin wollte ich mich nicht verlassen, denn allzubald wurde mir klar, daß auf dieser Welt jedem Rasputin ein Goethe gegenübersteht, daß Rasputin Goethe oder der Goethe einen Rasputin nach sich zieht, sogar erschafft, wenn es sein muß, um ihn hinterher verurteilen zu können.

Engl. I didn’t want to rely on Rasputin alone, because it soon became clear to me that in this world, every Rasputin is confronted by a Goethe, that Rasputin draws Goethe, or Goethe draws a Rasputin after him, even creating one, if necessary, in order to be able to condemn him afterward. (Grass, Günter: The Tin Drum: A Novel. Luchterhand, 1974, p. 74.)

March 2020.

Corona, for now, was something Chinese or a beer regularly on discount at Delhaize.

I was watching a documentary about Günther Grass (°October 16, 1927, †Free City of Danzig, April 13, 2015, Lübeck, Germany) with my fellow German language and literature students at the Erasmus House in Leuven in a small white (unaired) room. The old but brand new book Die Blechtrommel was waiting for each student (yes, only women). I had to do special and bought a second-hand copy, thinner and yellower, with a coffee spot on the cover. Something that attracted attention, among all the pristine white, unread books. An earlier printing, a printing closer to when the words flowed from Grass’ pen.

My German Literature professor frowned when I answered “das Fragment über den Pferdenkopf mit den Aale” (the fragment about the horse’s head with the eels) as he asked me which fragment I wanted to discuss as an exam paper.

Context:In the story, Oskar and his parents are watching a fisherman in the sea, who at one point fishes a dead horse’s head out of the water, with eels writhing in it. Like Oskar’s mother, I gagged at the image of the rotten head. That’s why I discussed it. Not to horrify my professor again, but because for me it was another ultimate example of the power of language. You have a page there that instantly disgusts you to the tip of your toe. A few sentences that on some thought refer to Freud and to Greek Mythology. I loved to keep looking for new layers in the story. New layers in one sentence, sometimes. Letters black and white that could refer to dozens of things.

It was when I turned the last page of that book that I realized I loved nothing more than being involved with literature, more specifically German and Dutch. And I have always retained that love. I don’t know if I will ever be as intensely involved with literature as I was in my education, but I believe that one’s passion will always get one somewhere. People sometimes forget what the power of literature and language is. It is thanks to literature that we collide with situations and cultural differences that we would never have collided with otherwise. It is thanks to literature that we trigger empathy in our brain. It is thanks to literature that cultures, lifestyles, ways of thinking meet and the author’s monologue can grow into a dialogue. Indeed, you cannot operate a human being with literature, invent a technological gadget. But, literature is an indirectly necessary contribution to society. A fundamental building block of that society. Amen.

H.B.

Recente bijdragen

Hanna Brems

Hanna Brems (b. 1999) is an old soul in the guise of a cheerful young lady. By day she works as a copywriter, but at night her creative writing comes […]

I call myself

My name is: Hanna. I call myself: broom in the plural. I call myself: yellow. I call myself: bush with buds, between which the wind strokes toward […]

Looking Up

Peter emails me a picture of the clouds, which he sees from his desk, along with the message: look at it and reflect, Hanna. I looked at the picture, […]

Alle auteurs

- Olivier Lichtenberg

- A Magical-Realist Portrait of Erembodegem, a Belgian village

- ADHD

- Advice from the doctor

- African poetry

- AIDS activism and gay emancipation

- Bibliography of Chris

- Bibliography of Olivier

- Bibliography of Patrick

- Biography of Chris

- Biography of Olivier

- Biography of Patrick

- Blackout poetry

- Blogs

- Chris' Stage

- Columns

- Covid

- Dirk van Babylon Newsletter

- Double calling

- Essays

- Fragile light

- Hanna's Mind Wanderings

- Incapacity for work

- Late Pasquino's

- Lectures

- LEIF doctor

- Liechtensteiner

- Medical newsletter

- Memoirs of a general practitioner

- Miguel Molinos

- Moctines

- Musings

- Myriad

- Patrick's Stage

- Practice in Erembodegem

- Resignation

- Short Stories

- Sleep problems

- Sonnets

- Sprawl Month

- Substance abuse and addiction

- Synchronicities

- Travel

- Vi to

- Vögels

- Voluntary euthanasia

- Weltschmerz

- Wormwood or The dose makes the poison

Over de auteur

Other works by our writers

- February 2026 (1)

- December 2025 (2)

- November 2025 (2)

- October 2025 (6)

- September 2025 (4)

- August 2025 (12)

- July 2025 (2)

- March 2025 (3)

- December 2024 (10)

- November 2024 (6)

- October 2024 (3)

- April 2024 (20)

- May 2021 (1)

- February 2021 (3)

- January 2021 (5)

No comments have been posted yet!